How Sex Work Became Forbidden Business

Researched by Yaeesh Collins and Isabella Liss

Written by Isabella Liss

Photographs by Yaeesh Collins

Our relationship with sex isn’t exclusively sexual. Our sexuality is also tied to political, economic, cultural, and religious beliefs. Throughout history, there have been many different perceptions of sex work, inspiring varied views on sex-related activities. So why have we adopted a Christian perspective?

Sex & Money

Contrary to popular belief, prostitution is not “the world’s oldest profession”. This is more likely medicine or midwifery. Prostitution came about with the growing dependence on economic markets, and has been largely absent from cultures that didn’t trade in physical money. (After all, without capital, there would be no need for any professions). Linguists have regularly found that words associated with prostitution in various cultures originate from the time that they were colonised.

Communities of Northern Thailand such as the Hmong largely accept that sex is for purely reproductive — not recreational — purposes. Hmong men purchase brides by paying money or silver to her family, a custom that represents compensation for generations of women’s breast milk that has nourished a lineage’s children. Although this is now viewed as a man paying for a woman he should have sex with, it was never associated (linguistically nor culturally) with “prostitution”, but rather tradition.

The Maori of New Zealand knew no concept of “prostitution” until European colonisers arrived, and began trading muskets for sexual favours. Those that engaged in what was deemed to be “explicit”, or in sex outside of the heterosexual “norm”, invoked the term “aitia”, meaning “sexual joy”. Similarly, prior to being colonised, the Dyak people of Borneo had no term for prostitution. Polygamy is strictly prohibited, and single men and women must rest in separate rooms. A “prostitute” is referred to as an unmarried person who sleeps in a “common room”. As recently as the late 1800s, Christian missionaries were inventing new words to indoctrinate Hawaiian islanders, discouraging practices such as infidelity. These instances led historians to believe that prostitution as we know it (for monetary income) is in fact a newer profession than once thought.

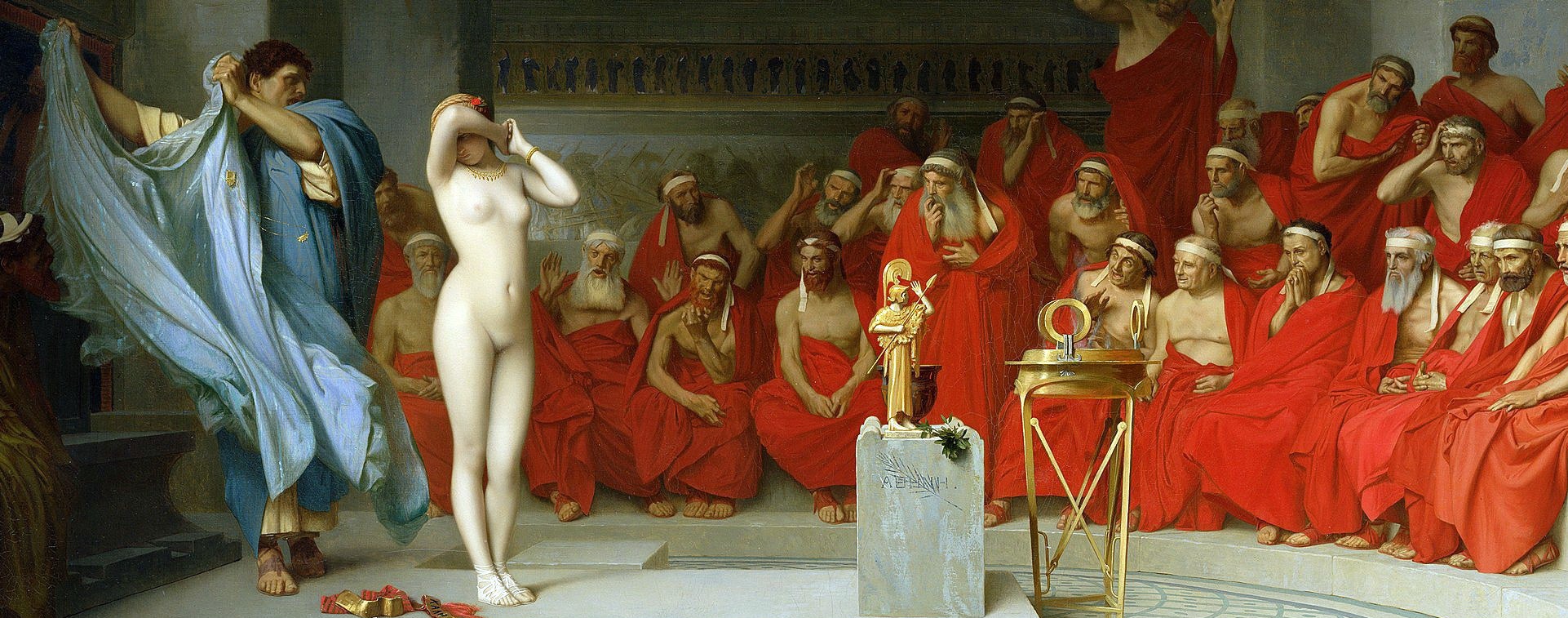

Ancient civilisations that practised prostitution include the Greeks, Japanese and Sumarians. But the range of skills needed to participate in sex work were very different. Hetaera women were highly educated, unlike other Greek women of their time. They were also required to pay tax on their profits. Japanese Geisha were originally male (later female) entertainers of the 18th century, performing sex acts, dancing, singing, poetry, and even calligraphy. Sumarian records hold the earliest mention of “prostitution” — around 2400 BC. These scripts describe brothels run by priests in Mesopotamian temples. Again, linguistically, they would not have harboured a job description like “prostitute”, and were revered for having sacred careers.

Prostitutes are common subjects of Impressionist art of the 1800s, due to their popularity among the bourgeoisie. Courtesans (what we may today refer to as an “escort”) were painted wearing fine jewellery in the luxurious apartments of their male clients. The figure of the sex worker in these paintings symbolised modernity, class, wealth, and power over the wealthiest of men. In modern art, portraits of sex workers informed some of Picasso’s most famous and controversial works.

Prostitution is just one of many forms of sex work (although arguably, the most popular). When we examine sex as a currency of its own, this by far predates prostitution. Human ancestors have been trading in sexual favours since the dawn of time. For these reasons, it is more accurate to describe sex itself as the world’s oldest currency, rather than assuming prostitution, as we know it, is an ancient profession.

When did sex work become taboo?

The topic of conversation wasn’t always off-limits. In fact, for most of human history, both sex and sex work were viewed as integral elements of art and culture. We see from some of the historical examples above that many different peoples participated in sex work, regardless of gender, ethnicity, or geography. Often, it was viewed as a sacred art, a religious or cultural ritual, and subject to remuneration. This is a far cry from the perceptions of sex work that come to mind today. Think immoral, uncultured, dirty or indecent.

During the Middle Ages in Europe, sex work was tolerated, but not celebrated. By the time of the 16th century Protestant Reformation, attitudes had changed and regulations were enforced. Some believe this was inspired by the writings of Martin Luther, a prominent theologian and leader of the reformation. The great indulgences of The Catholic Church angered him. Luther began to advocate for sexual monogamy, marriage, and regulation of women’s bodies in the name of Christianity. This eventually informed the ideas of immorality, chastity, classism and patriarchy that the British Empire brought to colonised nations. In recent years, it has been argued that Luther’s writings were not necessarily intent on imposing such regulations and worldview. Instead, he simply aimed to dismantle the hierarchy within the Catholic Church through removing indulgences that clergymen took part in — one of these being prostitution.

Portraying sex work in a negative light has resulted in the oppression of sex workers through discriminatory legislature, and widespread condemnation. It is important to remember that the socio-economic, cultural, and religious viewpoints we associate with sex work and prostitution are not by any means universal, and likely based upon newer historical developments.