A Glimpse Inside Cape Town’s Sex Work Community

By Isabella Liss

Photographs by Yaeesh Collins

Meet the young people who have found lucrative job opportunities in the industry, challenging how we label sex workers, and how sex workers classify themselves. They belong to a community fraught with complexities and identity politics. We discuss how they perceive this, and how it affects their occupation.

Cohen* (27) and Nico* (27) both identify as non-binary, and live together as primary partners within a polyamorous relationship. Nico is an escort, and usually presents as female when servicing private clients. Both work from home (never street work), but are taking a break due to COVID-19 social distancing measures. Cohen also works as a school teacher.

*Names have been changed. Cohen identifies as both he/him and they/them, while Nico identifies as they/them.

The How & Why

There are estimated to be over 150 000 sex workers practising in South Africa, most of whom began working during adolescence. Financial need, abuse, desperation, and addiction are what we commonly assume to be reasons for practising. But there are increasing numbers of young people who have seen economic opportunity, and are breaking this stereotype. Their journeys into the industry may seem “unconventional” to outsiders.

While taking an undergraduate gender studies course, Nico was introduced to the controversial topic of feminist pornography. Intrigued, they began performing in experimental films and feminist porn. “A lot of people who were into arts and filmmaking — they went into sex work. Dancers, people that knew they had the background and capacity to brand themselves and make a business out of it,” says Nico of their student peers. This led to stripping, and eventually full-service sex work. Years later, Nico would encourage their now partner, Cohen, to get involved. Averaging R800 per blowjob in the Southern Suburbs, Cohen is able to maximise their income in minimal time. “Money. Money is the best part about it,” he insists.

Cohen and Nico’s income from sex work has allowed them to travel overseas, and contributes towards their living expenses and university fees. Nico has recently completed a Master’s degree, while Cohen now teaches. They rent a house in the plush suburb of Tamboerskloof, something that few young adults in Cape Town can afford without assistance. But while they have achieved financial independence and their desired standard of living, they warn against romanticisation. “This is also a job. Sex work isn’t a passion of mine,” Cohen says. “My body is just as tired as it is from teaching.” It’s clear that this is not a fun or adventurous occupation of little effort. “There’s nothing glorified about it,” Cohen says.

Nico believes sex work may present an additional benefit to transgender and non-binary people. As well as being able to make the greatest amount of money in the shortest space of time, sex work initially offered them an attractive career opportunity because they were not made to present in a gendered work environment. Due to failing education systems in South Africa, the youth unemployment rate currently sits at over 48%. Working-class citizens often take up jobs like domestic work, waitressing, or retail assistance. Unskilled workers are made to fit into specific gender roles, or serve the public in gendered apparel. “I can be the gender that I want to be when I’m a sex worker,” Nico declares. They suggest this has contributed to the popularity of sex work in queer communities. While sex work is often more dangerous, it provides a better-paying alternative, because the worker is not ostracised for their gender identity, nor judged or made to feel uncomfortable in mandatory workwear.

Nico acknowledges that this is difficult to achieve if one wants to earn within a higher income bracket — greater than an unskilled worker. Here, escorting can be more limiting than other forms of sex work. As a result, Nico has made the choice to present as female to garner more clients. They believe that this market of men desire a particular image — a pretty white woman that adheres to Western beauty standards. Long straightened hair, shaven armpits, and French-tipped nails are the sacrifices Nico's made for greater earnings. “I was really sad about it, because it was a gendered thing I’ve fought for since [being] a teenager,” they reflect. While it can be a line of work that affirms one’s gender identity, it can also persistently challenge one’s identity. Nobody is truly empowered, or provided with limitless agency in their work. “They want to make you the version of yourself that they want you to be. And it reflects the things that they say about you.” Nico’s clients refer to them as everything, from “curvy” to “strong” and “skinny”. “They reflect their fantasies upon you. And if you’re smart you’ll play into it. And you’ll get another booking.”

Community Complexities

Cohen acknowledges that the support of their community has been integral to their financial and emotional wellbeing. “The sex work community is my backbone. It’s everything I need to survive in the work. Sex work is difficult . . . if I didn’t have the community that I had or the pricing on how I should price my blowjobs, I would’ve been earning way less money and that would’ve deterred me from doing any kind of sex work.” It also provided connections, and people to relate to. “That really helps. I don’t know of a sex worker that wouldn’t want to talk after having a John over,” Cohen continues. (A “John” is the generic slang term used by sex workers to refer to the client.) But as with any niche job, participants face a niche set of challenges. Nico is pragmatic, saying, “It’s identity politics — the same way it plays out in any other group.”

The community can also be divisive. Cohen and Nico refer to this as the “Whore-archy”. Those who do things typically thought of as sex work, but manage to avoid the act of having sex while acquiring the same goals, may consider themselves “better” than “traditional” sex workers. This could refer to sugar babies who have an older man paying their rent in exchange for friendship rather than sex. Or dominatrixes and strippers who do not have sex with clients. In turn, traditional sex workers frown upon those who do this, even questioning the legitimacy of their practice if it doesn’t involve penetrative sex. They may judge others for engaging in penetrative sex when it is not their place to do so. (Traditionally, club management discourages dancers and strippers from having sex with clients as a safety precaution. It is not the norm for strippers to provide full-service sex work.) Cohen refers to these attitudes as “whore-phobia”. “There’s a line that’s arbitrarily drawn between sex workers that doesn’t have to be there,” says Nico. You’re damned if you do, and you’re damned if you don’t. People become afraid to speak about the specifics of their sex work, or difficulties and dilemmas that they face in fear of being judged. These ideas then contribute to the isolation that many sex workers experience.

Like most South African circles, the community is further divided because of race, gender, and class. Street workers earn less than wealthier sex workers who are able to service clients in hotels, or their own homes. Black women account for 49% of unemployed people between the ages of 15 and 34, and many turn to sex work. As a result, white, cisgender prostitutes are uncommon. Because they are in-demand, they have the ability to charge more. Cohen and Nico find that marketing themselves to “the lowest common denominator” works best, providing the most bookings and best pay. Usually, these are clients who seek Western beauty standards and traditional gender roles, further disadvantaging any non-white or queer sex workers. This also means fetish work is hard to come by. Sex workers should be fit, and present a performance that affirms male client’s masculinity. Anyone overweight or unwilling to subscribe to societal norms will find it difficult to make a regular income from escorting in Cape Town.

Conversely, while travelling the United States, Cohen (who identifies as coloured) and Nico (white) found the relationship between race and income to be reversed. Cohen was sought after for appearing “exotic” among communities of majority white sex workers, and earned more than Nico. Cohen then returned to South Africa with this in mind, and marketed themself amongst foreign gay men. (South Africa has become a gay tourist destination due to being one of few countries with marriage equality explicitly stated in our constitution. Cape Town is renowned as “LGBTQ-friendly”, with it’s own Pride festival and gay beaches. Tourists who come to experience this often seek out “exotic” sex workers.)

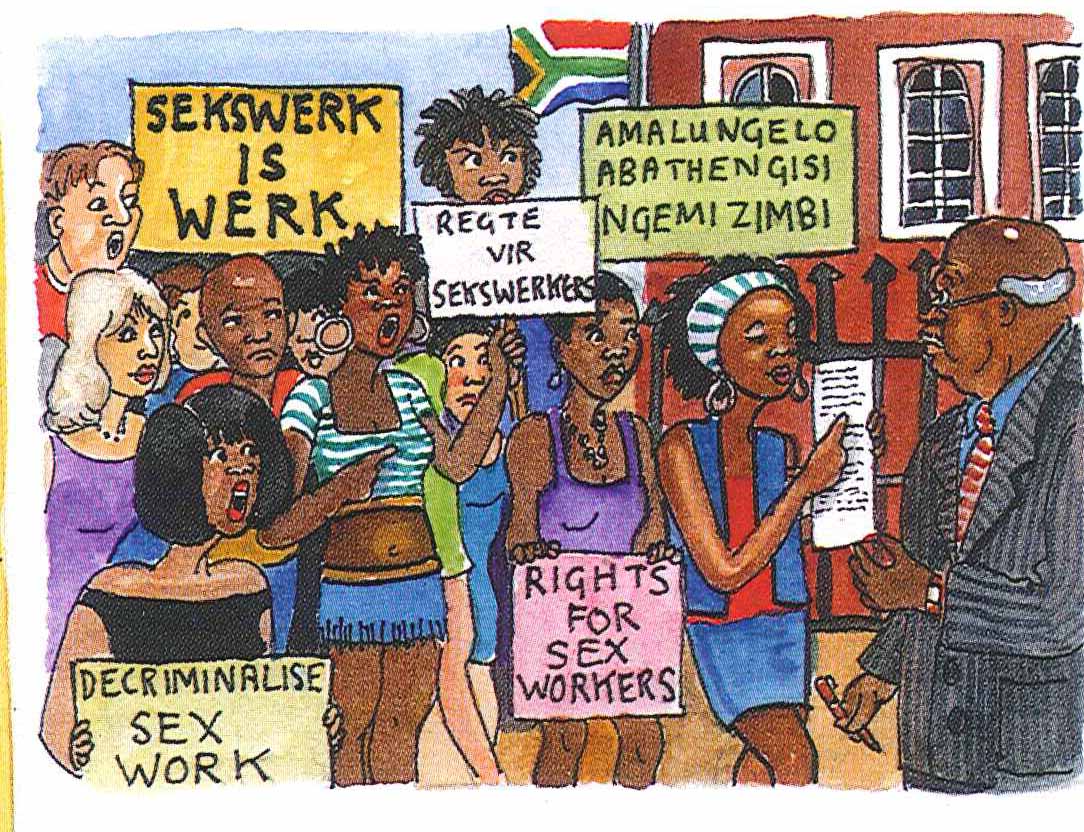

Nico believes that these divisions make it difficult to form a union or body to voice sex worker’s rights. Different people prioritise concerns that are of interest to them, be it race, class or gender issues. This is further complicated by the fact that the type of sex work one offers is dependent on the individual, their personal values, and degree of experience. Workers may be discriminated against through a variety of factors, but also critique each other through a variety of factors. There is very little consensus among sex workers themselves. While outsiders to the community debate whether sex work is even a legitimate form of labour, who or what defines a sex worker remains a topic of debate within the community itself.

Defining Oneself

Cohen and Nico have had various characters imposed on them, crafted personalities for their work, and navigated their own identities within their relationship. So what have they come to realise a sex worker is? It is perhaps realising that we should be drawing parallels, rather than imagined boundaries. “You want a line to be drawn,” Cohen says. “Anxieties that we have as a society, the anxieties about what is work what isn’t work, are heaped on sex workers in a way that they’re not heaped on other informal workers. And that’s an issue of morality.” Rather than nitpicking, the first step is to recognise sex workers as diverse human beings and contributors to society, however they choose to operate. Nico elaborates: “I feel like we should just break down all those boundaries and be using sex and sexuality as a bargaining tool, and not something to be looked down upon [as] it happens every day. It happened before us and it will happen after us. It will happen regardless of whether people call themselves sex workers.”